Note: The following story contains descriptions of sexual assault that some readers might find upsetting.

It was Andrew's sixth night of freshman year at Brown University when he was assaulted by a male student in his dorm bathroom. When Andrew brought on-campus charges, his assailant was expelled.

Unlike myriad students who report mishandled cases in the burgeoning national campaign against sexual assault, Andrew initially believed his case was handled appropriately.

But after The Huffington Post discovered Andrew’s assailant had previously been found responsible for assaulting two other students and had not been expelled, Andrew was devastated.

Andrew has decided to share his story in hopes that victims of assault -- and specifically male victims -- be taken more seriously.

“It’s time to include male survivors’ voices,” he said. “We are up against a system that’s not designed to help us.”

In the early hours of Sept. 5, 2011, Andrew, who asked that his last name be withheld, was up late excitedly chatting with his hallmates in Keeney Quad, one of two main freshman housing units. Jumping from room to room, Andrew admired the varied displays his classmates had on their walls. In his room, Andrew had put up Art Deco travel posters and a screen print of neighborhoods in his hometown of Washington, D.C.

Around 5 a.m., his classmates returned to their rooms while Andrew headed to the communal bathrooms to brush his teeth. Halfway down the hall, a male student he didn’t recognize passed him. Not thinking much of it, Andrew entered the bathroom and began to wash his hands.

A knock on the door surprised him. The bathroom required a dorm key, so anyone who lived in the building should have been able to get inside. Andrew opened the door. It was the same student he had seen in the hall.

Andrew went back to the sink, and the student approached him. “You’re hot,” Andrew remembers him saying. The student propositioned him but Andrew politely declined.

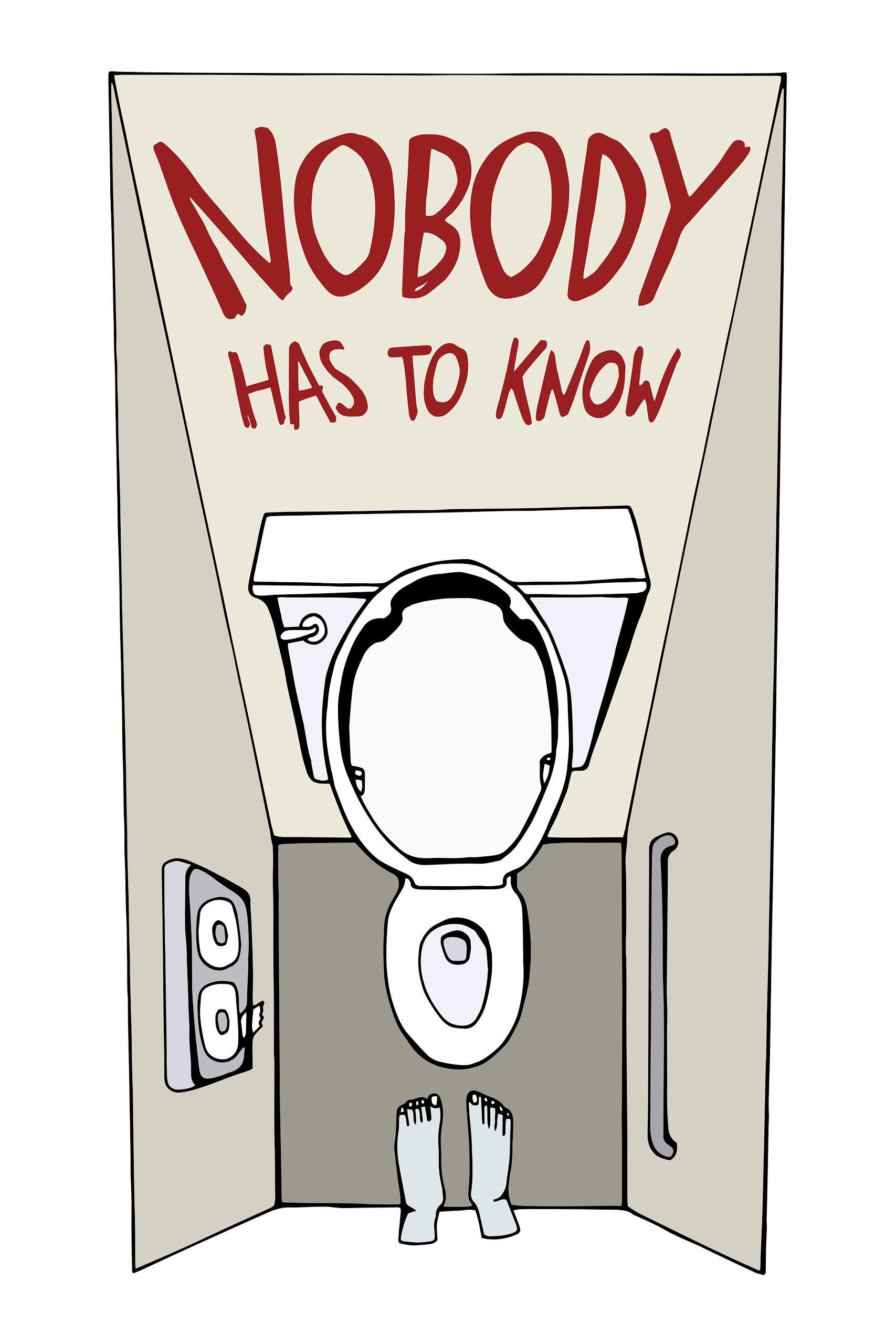

(Illustration by Sage Barlow for HuffPost)

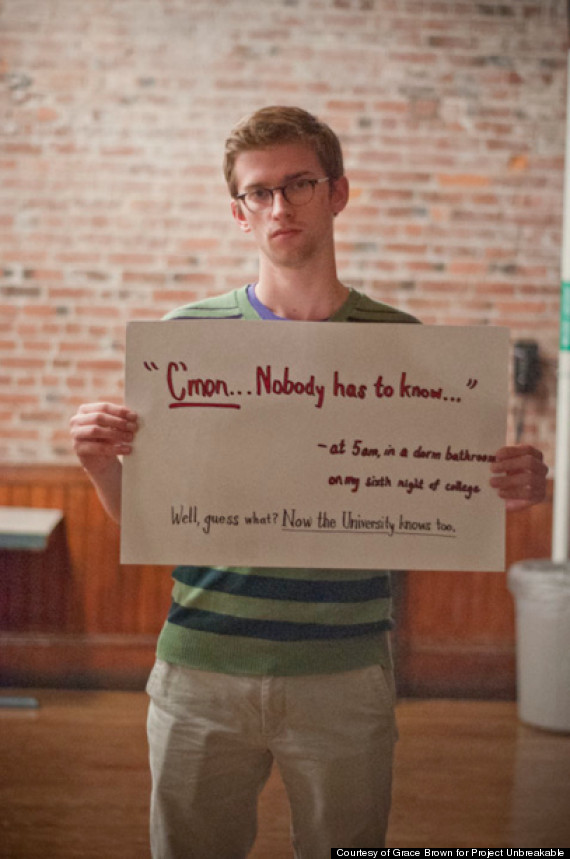

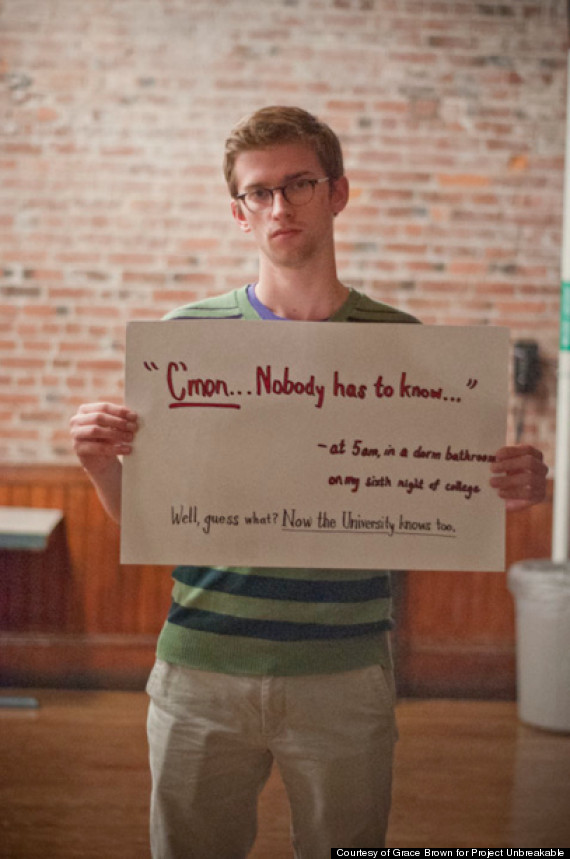

“Nobody has to know,” the student said.

He came up behind Andrew, grabbed his crotch and moved him into the bathroom stall. Frozen, Andrew protested but did not fight back, scared of what would happen if he did.

For 15 minutes the stranger assaulted him.

Andrew has a hard time articulating what he felt during the assault. All he remembers is being unable to speak or act. “I just remember focusing on the stall door, knowing that he was between me and my escape."

When the assault was over, the assailant “just left.” Andrew remembers resting his head against the bathroom stall and listening to the buzz of the fluorescent lights as he tried to reconcile what had just happened to him.

“I didn’t even know his name," Andrew said. "I didn’t know who he was. Nobody saw anything.”

Andrew later found out the assailant’s name through a mutual friend. During the hearing process he also learned that his assailant was a sophomore who had been visiting a residential adviser in the dorm earlier that night.

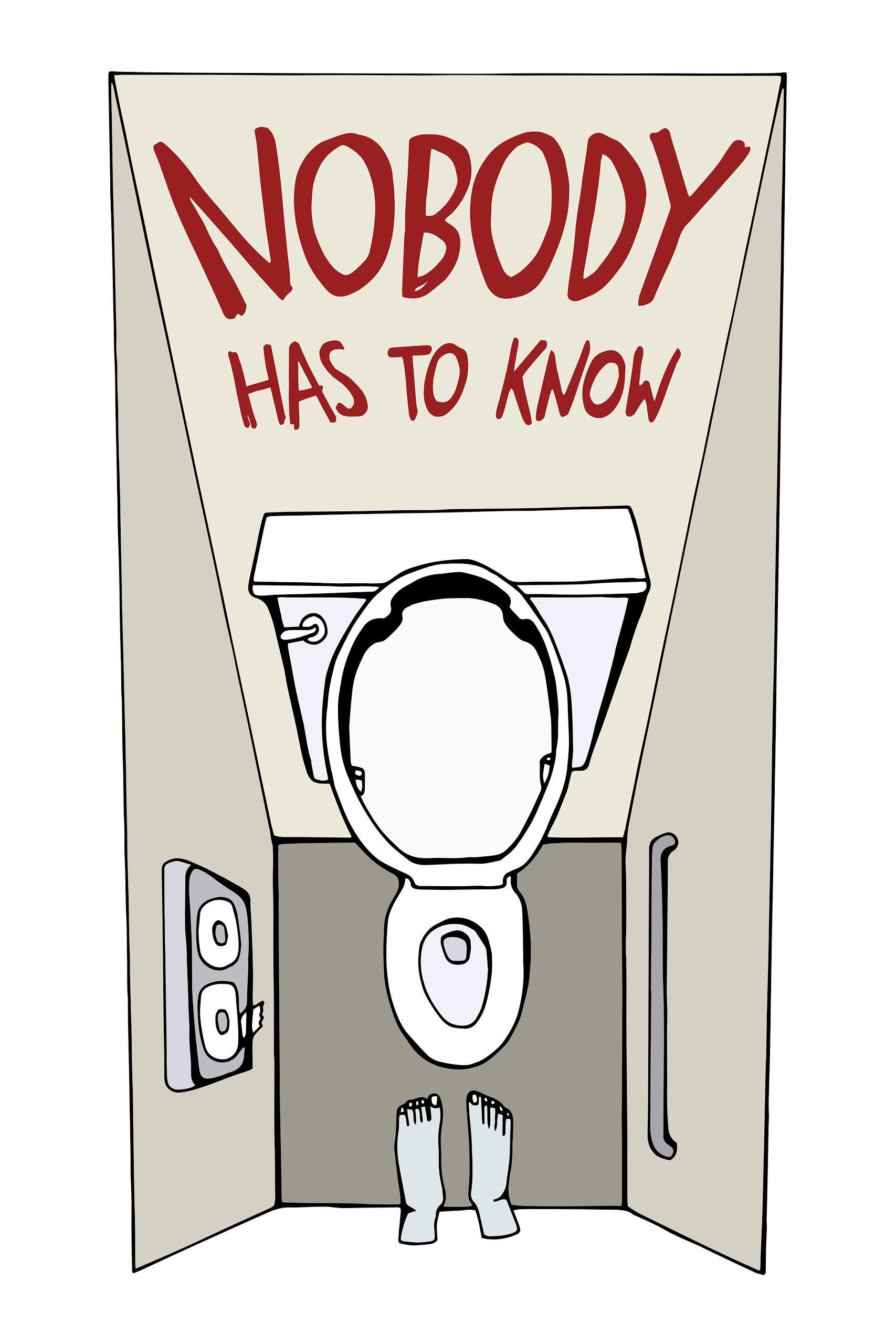

The day after the assault, Andrew told his friends what happened, but joked that it was a “5 a.m. hookup in the bathroom.” It was easier to deal with the shame if he felt control over the situation. At 8 p.m. Andrew and his classmates were required to attend a mandatory orientation meeting entitled “Understanding Sexual Assault.”

Andrew remembers feeling isolated in the auditorium populated by his peers. “It was a sad twist of irony,” he said.

It was Andrew's sixth night of freshman year at Brown University when he was assaulted by a male student in his dorm bathroom. When Andrew brought on-campus charges, his assailant was expelled.

Unlike myriad students who report mishandled cases in the burgeoning national campaign against sexual assault, Andrew initially believed his case was handled appropriately.

But after The Huffington Post discovered Andrew’s assailant had previously been found responsible for assaulting two other students and had not been expelled, Andrew was devastated.

Andrew has decided to share his story in hopes that victims of assault -- and specifically male victims -- be taken more seriously.

“It’s time to include male survivors’ voices,” he said. “We are up against a system that’s not designed to help us.”

In the early hours of Sept. 5, 2011, Andrew, who asked that his last name be withheld, was up late excitedly chatting with his hallmates in Keeney Quad, one of two main freshman housing units. Jumping from room to room, Andrew admired the varied displays his classmates had on their walls. In his room, Andrew had put up Art Deco travel posters and a screen print of neighborhoods in his hometown of Washington, D.C.

Around 5 a.m., his classmates returned to their rooms while Andrew headed to the communal bathrooms to brush his teeth. Halfway down the hall, a male student he didn’t recognize passed him. Not thinking much of it, Andrew entered the bathroom and began to wash his hands.

A knock on the door surprised him. The bathroom required a dorm key, so anyone who lived in the building should have been able to get inside. Andrew opened the door. It was the same student he had seen in the hall.

Andrew went back to the sink, and the student approached him. “You’re hot,” Andrew remembers him saying. The student propositioned him but Andrew politely declined.

(Illustration by Sage Barlow for HuffPost)

“Nobody has to know,” the student said.

He came up behind Andrew, grabbed his crotch and moved him into the bathroom stall. Frozen, Andrew protested but did not fight back, scared of what would happen if he did.

For 15 minutes the stranger assaulted him.

Andrew has a hard time articulating what he felt during the assault. All he remembers is being unable to speak or act. “I just remember focusing on the stall door, knowing that he was between me and my escape."

When the assault was over, the assailant “just left.” Andrew remembers resting his head against the bathroom stall and listening to the buzz of the fluorescent lights as he tried to reconcile what had just happened to him.

“I didn’t even know his name," Andrew said. "I didn’t know who he was. Nobody saw anything.”

Andrew later found out the assailant’s name through a mutual friend. During the hearing process he also learned that his assailant was a sophomore who had been visiting a residential adviser in the dorm earlier that night.

The day after the assault, Andrew told his friends what happened, but joked that it was a “5 a.m. hookup in the bathroom.” It was easier to deal with the shame if he felt control over the situation. At 8 p.m. Andrew and his classmates were required to attend a mandatory orientation meeting entitled “Understanding Sexual Assault.”

Andrew remembers feeling isolated in the auditorium populated by his peers. “It was a sad twist of irony,” he said.

At

first, Andrew berated himself, wondering if he could have done more to

stop it. But after a couple months he started feeling like himself

again, excelling in his introductory course on Urban Studies and joining

groups like the Queer Alliance, the Brown University Chorus and a coed

literary fraternity.

Things took a turn in the spring when Andrew was cast in a campus production of "Don Pasquale" and attended rehearsals nightly on the north side of campus, where his assailant lived -- and seeing him “almost every single time” he was there.

On the morning of Feb. 29, 2012, he had a panic attack. “I got in the shower and suddenly started shaking and could only see in front of me and probably couldn't have told you where or who I was.”

Andrew started meeting regularly with a counselor, but initially chose not to share the assailant’s name, as he was not ready to pursue a campus hearing. But in May, after a couple months of counseling, he decided to file a formal complaint with the university. The hearing was held the following November.

Andrew’s assailant participated via phone as, unbeknownst to Andrew, he was on suspension for two other cases of sexual assault.

The two other victims, Brenton (who would only give his first name), and another student who requested to remain anonymous, said they filed a joint complaint in December 2011. They had hearings for their cases in March 2012; the university found the assailant responsible for sexual misconduct in both cases and suspended him until the following December.

“I was happy that he got suspended, but I didn’t think it was enough. I knew there were even more people he had gotten to,” Brenton said.

After Andrew’s hearing in November, the university found the assailant responsible for a third case of sexual misconduct and expelled him. The assailant appealed all three sanctions and was rejected. He declined to comment for this article.

The timeline of all three assaults was as follows:

Things took a turn in the spring when Andrew was cast in a campus production of "Don Pasquale" and attended rehearsals nightly on the north side of campus, where his assailant lived -- and seeing him “almost every single time” he was there.

On the morning of Feb. 29, 2012, he had a panic attack. “I got in the shower and suddenly started shaking and could only see in front of me and probably couldn't have told you where or who I was.”

Andrew started meeting regularly with a counselor, but initially chose not to share the assailant’s name, as he was not ready to pursue a campus hearing. But in May, after a couple months of counseling, he decided to file a formal complaint with the university. The hearing was held the following November.

Andrew’s assailant participated via phone as, unbeknownst to Andrew, he was on suspension for two other cases of sexual assault.

The two other victims, Brenton (who would only give his first name), and another student who requested to remain anonymous, said they filed a joint complaint in December 2011. They had hearings for their cases in March 2012; the university found the assailant responsible for sexual misconduct in both cases and suspended him until the following December.

“I was happy that he got suspended, but I didn’t think it was enough. I knew there were even more people he had gotten to,” Brenton said.

After Andrew’s hearing in November, the university found the assailant responsible for a third case of sexual misconduct and expelled him. The assailant appealed all three sanctions and was rejected. He declined to comment for this article.

The timeline of all three assaults was as follows:

Brown has recently been in the news for accusations of mishandled cases of sexual assault, notably that of Lena Sclove, which prompted a federal Title IX investigation.

In Sclove's case, the accused student was found responsible for two counts of sexual misconduct and suspended for two semesters. Similarly, the student who assaulted Brenton and the anonymous victim was merely suspended for just over one semester.

Brown’s failure to impose a sufficient sanction was unsurprising to Andrew but upsetting nonetheless. “I wish they had taken it seriously the first one or two times,” he said. “The process weighed on me from April to November. ... I could’ve had days of my sophomore year that I didn't have to drag myself out of bed every morning. … To know that [the hearing process] could have been prevented if they had expelled him the first time is incredibly upsetting. My sophomore year could have been totally different.”

Brown’s president, Christina Paxson, recently sent a letter to the Brown community outlining revisions to Brown’s sexual assault policy, including that a student given a sanction that includes separation from the university would be immediately removed from campus residences (though not necessarily barred from campus). The letter also included clearer guidelines on how the university determines a sanction, but it didn’t determine specific sanctions for violations of sexual misconduct, leaving Andrew’s concern unaddressed.

In a statement emailed to The Huffington Post, Brown University said it could not comment on the individual cases.

“The circumstances of each case are taken into account by the conduct board and adjudicated under our current sanctioning guidelines, which are reviewed regularly,” the statement said. “We believe our process is the right one for our University and we remain committed to doing all we can to keep our community safe and to being a leader in establishing best practices.”

In Sclove's case, the accused student was found responsible for two counts of sexual misconduct and suspended for two semesters. Similarly, the student who assaulted Brenton and the anonymous victim was merely suspended for just over one semester.

Brown’s failure to impose a sufficient sanction was unsurprising to Andrew but upsetting nonetheless. “I wish they had taken it seriously the first one or two times,” he said. “The process weighed on me from April to November. ... I could’ve had days of my sophomore year that I didn't have to drag myself out of bed every morning. … To know that [the hearing process] could have been prevented if they had expelled him the first time is incredibly upsetting. My sophomore year could have been totally different.”

Brown’s president, Christina Paxson, recently sent a letter to the Brown community outlining revisions to Brown’s sexual assault policy, including that a student given a sanction that includes separation from the university would be immediately removed from campus residences (though not necessarily barred from campus). The letter also included clearer guidelines on how the university determines a sanction, but it didn’t determine specific sanctions for violations of sexual misconduct, leaving Andrew’s concern unaddressed.

In a statement emailed to The Huffington Post, Brown University said it could not comment on the individual cases.

“The circumstances of each case are taken into account by the conduct board and adjudicated under our current sanctioning guidelines, which are reviewed regularly,” the statement said. “We believe our process is the right one for our University and we remain committed to doing all we can to keep our community safe and to being a leader in establishing best practices.”

For

all the focus on campus sexual assault in recent years, male victims

have been frequently absent from the news coverage, except for the most

tragic cases, like that of Trey Malone, an Amherst College student who

committed suicide after his assault.

One study shows rape victims are 13 times more likely than non-crime victims to have attempted suicide. Jennifer Marsh, vice president of victims services at Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network, the largest anti-sexual-assault organization in the nation, said both men and women who survive sexual assault face similar psychological effects -- but there are some differences. “Male survivors who are suicidal tend to use more lethal means,” Marsh said.

Studies show that one in five women has been the victim of attempted or completed rape in her lifetime, and that approximately 50 percent of transgender people experience sexual violence at some point in their lifetimes. But statistics vary on the incidence of sexual assault against men. According to a study by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, of 5,000 college students at over 130 colleges, one in 25 men answered "yes" to the question "In your lifetime have you been forced to submit to sexual intercourse against your will?" Other organizations, such as 1in6, an advocacy group for male survivors, put the estimate much higher, at one in six males before the age of 18.

Steve LaPore, founder and director of 1in6, believes male sexual assaults are underreported because the issue is still taboo. While women have “really moved the ball forward,” resulting in a heightened awareness about sexual assault against women and children, it’s an awareness that doesn’t include men as victims, he said.

“Culturally we still don’t want to see men as vulnerable or hurt,” LaPore explained. “We tell little boys and men to pull themselves up by their bootstraps.” Because of the stigma, he said, there are fewer resources available for male victims.

LaPore was not surprised by the fact that Andrew’s assailant initially received a lighter punishment. “In many cases we find that it’s more difficult for men to be believed, or to take their case seriously,” he said. “I think we’ve done a pretty good job of seeing men’s roles as bystanders and preventers, but we don’t recognize men who are survivors of sexual assault and abuse.”

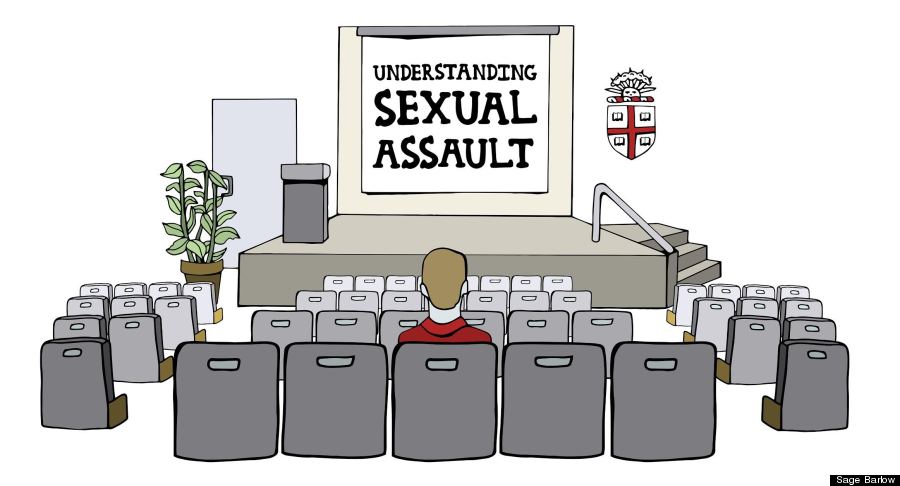

Clayton Bullock, psychiatrist and co-author of Male Victims of Sexual Assault: Phenomenology, Psychology, Physiology, found that male victims are also less likely to come forward or be taken seriously because of their physiological response to assault.

(Illustration by Sage Barlow for HuffPost)

“It is possible for men to get aroused and ejaculate when being assaulted,” Bullock said. “What’s particularly bewildering for the males is that if they ejaculated or were aroused during the assault, it adds a layer of shame or confusion in their culpability of their own victimization.”

Men also have difficulty with the language of sexual assault, according to Jim Hopper, instructor of psychology at Harvard Medical School and a founding board member of 1in6.

“There are words like ‘victim’ and ‘survivor’ that are hard to identify with, especially for men,” Hopper said. “For many men, they don’t want to be a 'victim' because it’s antithetical to what it means to be a real man.”

One study shows rape victims are 13 times more likely than non-crime victims to have attempted suicide. Jennifer Marsh, vice president of victims services at Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network, the largest anti-sexual-assault organization in the nation, said both men and women who survive sexual assault face similar psychological effects -- but there are some differences. “Male survivors who are suicidal tend to use more lethal means,” Marsh said.

Studies show that one in five women has been the victim of attempted or completed rape in her lifetime, and that approximately 50 percent of transgender people experience sexual violence at some point in their lifetimes. But statistics vary on the incidence of sexual assault against men. According to a study by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, of 5,000 college students at over 130 colleges, one in 25 men answered "yes" to the question "In your lifetime have you been forced to submit to sexual intercourse against your will?" Other organizations, such as 1in6, an advocacy group for male survivors, put the estimate much higher, at one in six males before the age of 18.

Steve LaPore, founder and director of 1in6, believes male sexual assaults are underreported because the issue is still taboo. While women have “really moved the ball forward,” resulting in a heightened awareness about sexual assault against women and children, it’s an awareness that doesn’t include men as victims, he said.

"We tell little boys and men to pull themselves up by their bootstraps."

“Culturally we still don’t want to see men as vulnerable or hurt,” LaPore explained. “We tell little boys and men to pull themselves up by their bootstraps.” Because of the stigma, he said, there are fewer resources available for male victims.

LaPore was not surprised by the fact that Andrew’s assailant initially received a lighter punishment. “In many cases we find that it’s more difficult for men to be believed, or to take their case seriously,” he said. “I think we’ve done a pretty good job of seeing men’s roles as bystanders and preventers, but we don’t recognize men who are survivors of sexual assault and abuse.”

Clayton Bullock, psychiatrist and co-author of Male Victims of Sexual Assault: Phenomenology, Psychology, Physiology, found that male victims are also less likely to come forward or be taken seriously because of their physiological response to assault.

(Illustration by Sage Barlow for HuffPost)

“It is possible for men to get aroused and ejaculate when being assaulted,” Bullock said. “What’s particularly bewildering for the males is that if they ejaculated or were aroused during the assault, it adds a layer of shame or confusion in their culpability of their own victimization.”

Men also have difficulty with the language of sexual assault, according to Jim Hopper, instructor of psychology at Harvard Medical School and a founding board member of 1in6.

“There are words like ‘victim’ and ‘survivor’ that are hard to identify with, especially for men,” Hopper said. “For many men, they don’t want to be a 'victim' because it’s antithetical to what it means to be a real man.”

A

friend of Malone’s at Amherst, who identified himself as Eric for this

article, said he was raped by his freshman-year roommate. After feeling

dissatisfied with the school’s handling of his case, Eric attempted

suicide by overdosing on Benadryl, but it didn’t work.

“I remember waking up to [my roommate] kissing the back of my neck, and I feel his erect dick behind me,” Eric recalled. “I turn around and am like, ‘What are you doing?’ And he says, ‘What are you doing in my room?’ And I said, ‘No, dude, you’re in my bed.’”

Eric feels he was targeted because of his sexuality. “I was very open about being gay, so I think that’s a big part of it; he assaulted me because he knew I was gay,” Eric said. “After that I felt like I couldn’t be as out as I was. He thought that was an invitation.”

Andrew, who identifies as queer, believes it’s more difficult for people to talk about queer victims of assault. “They don’t want to think that queer people exist to begin with, so the idea that sexual assault happens in those communities is something people don’t want to talk about,” he said. “There are some people who also believe [sexual assault] is punishment or retribution for being queer.”

The 2010 National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found about 40 percent of gay men, 47 percent of bisexual men and 21 percent of heterosexual men in the U.S. "have experienced sexual violence other than rape at some point in their lives."

Bullock says gay men are often targets of sexual assault because of gay-bashing, or because of conflicted feelings about the assailant's own attraction to other men in which they are “exorcising their internalized homophobia.”

And since the LGBTQ community is often perceived as promiscuous, it can be difficult for victims to come forward.

"The sentiment I hear the most and feel the most is that because we're being open about our sexuality, when someone assaults us it’s not an assault," Eric said. "Like, ‘Oh you were kind of asking for it,’ or ‘Are you surprised you got assaulted?’"

Eric struggled at Amherst in the immediate aftermath of his assault, eventually dropping out when the administration allowed his assailant to remain on campus. After leaving college, he joined the military and became an engineer. He’s feeling optimistic about what’s next, but he still feels the impact of what happened to him.

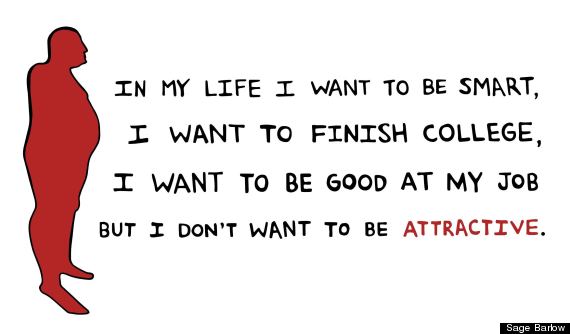

“You know ‘Carry That Weight’?” he asked, referring to Columbia University student Emma Sulkowicz’s campaign to raise awareness of college sexual assault by carrying a mattress around campus until her rapist is expelled. “How I imagine carrying my weight is physical weight. I actually gained a lot of weight, and part of that was intentional. It’s comforting for me being heavier and less looked at as a sex object. In my life I want to be smart, I want to finish college, I want to be good at my job. But I don’t want to be attractive.”

According to Marsh, Eric's sentiment is typical of both male and female victims.

“The idea that they don’t want any type of attention, or anything remotely resembling sexual advances," Marsh said. "I think there’s a fear that this could happen again. And if they make themselves so unappealing, they won’t get hurt the way they’ve been hurt before.”

“I remember waking up to [my roommate] kissing the back of my neck, and I feel his erect dick behind me,” Eric recalled. “I turn around and am like, ‘What are you doing?’ And he says, ‘What are you doing in my room?’ And I said, ‘No, dude, you’re in my bed.’”

Eric feels he was targeted because of his sexuality. “I was very open about being gay, so I think that’s a big part of it; he assaulted me because he knew I was gay,” Eric said. “After that I felt like I couldn’t be as out as I was. He thought that was an invitation.”

Andrew, who identifies as queer, believes it’s more difficult for people to talk about queer victims of assault. “They don’t want to think that queer people exist to begin with, so the idea that sexual assault happens in those communities is something people don’t want to talk about,” he said. “There are some people who also believe [sexual assault] is punishment or retribution for being queer.”

The 2010 National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found about 40 percent of gay men, 47 percent of bisexual men and 21 percent of heterosexual men in the U.S. "have experienced sexual violence other than rape at some point in their lives."

Bullock says gay men are often targets of sexual assault because of gay-bashing, or because of conflicted feelings about the assailant's own attraction to other men in which they are “exorcising their internalized homophobia.”

And since the LGBTQ community is often perceived as promiscuous, it can be difficult for victims to come forward.

"The sentiment I hear the most and feel the most is that because we're being open about our sexuality, when someone assaults us it’s not an assault," Eric said. "Like, ‘Oh you were kind of asking for it,’ or ‘Are you surprised you got assaulted?’"

Eric struggled at Amherst in the immediate aftermath of his assault, eventually dropping out when the administration allowed his assailant to remain on campus. After leaving college, he joined the military and became an engineer. He’s feeling optimistic about what’s next, but he still feels the impact of what happened to him.

“You know ‘Carry That Weight’?” he asked, referring to Columbia University student Emma Sulkowicz’s campaign to raise awareness of college sexual assault by carrying a mattress around campus until her rapist is expelled. “How I imagine carrying my weight is physical weight. I actually gained a lot of weight, and part of that was intentional. It’s comforting for me being heavier and less looked at as a sex object. In my life I want to be smart, I want to finish college, I want to be good at my job. But I don’t want to be attractive.”

According to Marsh, Eric's sentiment is typical of both male and female victims.

“The idea that they don’t want any type of attention, or anything remotely resembling sexual advances," Marsh said. "I think there’s a fear that this could happen again. And if they make themselves so unappealing, they won’t get hurt the way they’ve been hurt before.”

Like many other victims, Eric doesn’t think the punishment for sexual assault at colleges is sufficient.

“If we treated rape the way we treated plagiarism on college campuses, there would be minimal rape," Eric insisted. "They expel people all the time for plagiarism.”

However, punishment for rape is just one part of the solution. LaPore, founder of 1in6, believes resources need to be more easily accessible for men, including the way clinics and programs are named and advertised. “If we could become willing to be inclusive, we would see more men willing to come forward and say we would like some help,” he said.

Michael Rose, who was in the same coed fraternity as Andrew at Brown, believes the role of bystanders is also integral. “Making sure every space is a safe space” is important, he said. “If more people can be trained as bystanders, and feel comfortable intervening. That’s huge.”

Rose was surprised when Andrew told him about the assault. Despite Rose’s involvement in Brown’s Sexual Assault Peer Education program, Andrew was the first male survivor he had met.

“We were just together in the lounge and we had been talking about consensual sex and life on campus, and he mentioned to me he’d been assaulted his first semester," Rose said. "I was shocked at first. You never want it to happen, but especially not to someone you know."

Rose was one of the first people Andrew told about his assault. He told his parents about it the following summer and came out as a survivor to his friends on Facebook during his junior year, when he participated in an online campaign for sexual assault survivors called Project Unbreakable.

He also participated in “Carry That Weight” in solidarity with Sulkowicz’s campaign by carrying a stall door, since his assault occurred in a bathroom.

Both experiences helped Andrew in his healing process. Upon sharing his story, he received encouragement from his friends and family. "My parents were pretty supportive,” he said. “They reiterated the points that I was still valuable and it had no impact on how they thought of me."

Andrew

is now a senior at Brown. He’s finishing his concentration in Urban

Studies, writing a thesis on suburban poverty and completing an applied

music program. A sign on his dorm door reads, “Hi! Come talk to me about

sexual assault, consent, relationships or really anything.”“If we treated rape the way we treated plagiarism on college campuses, there would be minimal rape," Eric insisted. "They expel people all the time for plagiarism.”

However, punishment for rape is just one part of the solution. LaPore, founder of 1in6, believes resources need to be more easily accessible for men, including the way clinics and programs are named and advertised. “If we could become willing to be inclusive, we would see more men willing to come forward and say we would like some help,” he said.

Michael Rose, who was in the same coed fraternity as Andrew at Brown, believes the role of bystanders is also integral. “Making sure every space is a safe space” is important, he said. “If more people can be trained as bystanders, and feel comfortable intervening. That’s huge.”

Rose was surprised when Andrew told him about the assault. Despite Rose’s involvement in Brown’s Sexual Assault Peer Education program, Andrew was the first male survivor he had met.

“We were just together in the lounge and we had been talking about consensual sex and life on campus, and he mentioned to me he’d been assaulted his first semester," Rose said. "I was shocked at first. You never want it to happen, but especially not to someone you know."

Rose was one of the first people Andrew told about his assault. He told his parents about it the following summer and came out as a survivor to his friends on Facebook during his junior year, when he participated in an online campaign for sexual assault survivors called Project Unbreakable.

He also participated in “Carry That Weight” in solidarity with Sulkowicz’s campaign by carrying a stall door, since his assault occurred in a bathroom.

Both experiences helped Andrew in his healing process. Upon sharing his story, he received encouragement from his friends and family. "My parents were pretty supportive,” he said. “They reiterated the points that I was still valuable and it had no impact on how they thought of me."

Walking along the campus green, Andrew seems energized. He talks about

No comments:

Post a Comment